Caught Between Two Worlds: The Unique Experiences of Second-Generation Afghan Immigrants in Iran

Iran hosts a large population of Afghan immigrants, nearly five million people, according to a recent estimation (Sadeghi, 2024). Afghans have migrated to Iran to escape war or to flee the insecure social and political conditions in Afghanistan. Despite the historical and religious similarities between Afghan immigrants and their Iranian hosts, intergroup relations have not always been peaceful but hostile or, at some points, brutal, as reflected in anti-immigrant demonstrations and the burning of their homes (Ruhani et al., 2023). Among Afghan immigrants living in Iran, the second-generation ones — those born in Iran or who migrated during childhood — face unique challenges. Despite being raised in Iran and speaking Persian — the formal language of Iran — fluently, many of them still experience a sense of exclusion from Iranian society (Ashrafi & Moghissi, 2002; Farahani et al., 2023) and are considered outsiders by Iranian society (Ruhani et al., 2023). They face widespread discriminations in Iran that limit their social, educational, and economic prospects (Chatty, 2010; Sadeghi, 2008), so they often face complex challenges in shaping their identities and dealing with related issues.

This article provides a comprehensive portrayal of what second-generation Afghan immigrants in Iran experience, with a particular focus on their relations with the host society. Specifically, we focus on how these social identity loss processes — perceiving themselves as neither part of Afghan heritage nor part of Iranian society — impact their sense of belonging and well-being, their social networks, and their educational and economic opportunities.

Our research focuses on how second-generation Afghans define and see themselves in the Iranian context. Based on previous research (Haslam et al., 2018; Jetten et al., 2009), when individuals migrate to a new society or become part of groups within the host society, they face the challenge of negotiating their sense of self concerning the new social setting. Thus, they may seek to (a) maintain a sense of continuity with their cultural heritage (i.e., identify as Afghans) while also (b) form new social identities in the new context (i.e., identify as Iranians; Haslam et al., 2021; Smeekes & Verkuyten, 2015). For second-generation Afghans, previous group memberships, e.g., relatives and communities linked to the Afghan immigrants in Iran, can work as a protective shelter against negative outcomes associated with change.

For second-generation Afghans in Iran, we anticipated that feelings of identity incompatibility may be common since their Afghan identity may struggle to reconcile with their Iranian identity. The feeling of identity incompatibility hinders both identity continuity and identity gain in their post-migration lives. However, this experience may vary among Afghan immigrants. Those who struggle to acculturate to Iranian society might find valuable social and psychological support within the Afghan community in Iran, which in turn helps them navigate their challenges.

The data used in this research came from 23 in-depth interviews with Afghan adolescents between the ages of 16 and 19 (10 women) from March to April 2022. The first five interviews were exploratory, followed by subsequent interviews that focused on the emerging themes in previous interviews while being open to exploring new emerging themes. To analyse the data, we adopted a grounded theory approach following the guidelines proposed by Charmaz (2006). First, we created codes from the transcripts of the interviews and linked specific quotes to these codes. This flexible process allowed us to break down the data into smaller and more abstract parts. Then, we grouped these codes based on similarities and differences to identify broader themes. Finally, we organized these themes into distinct categories and connected all the subthemes to gain a complete understanding of the participants’ experiences.

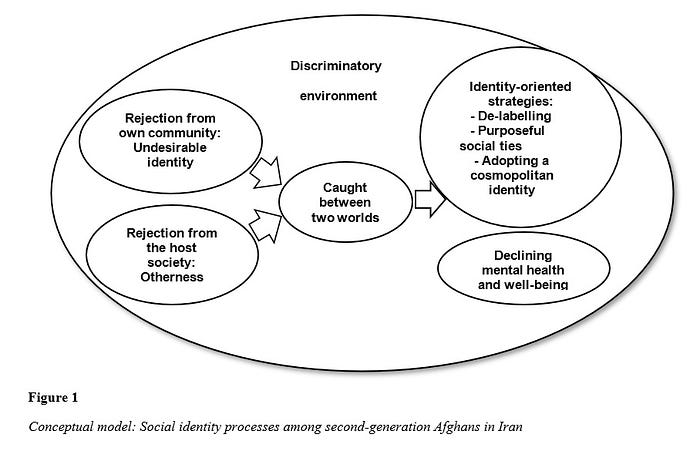

Figure 1 shows all extracted themes in one frame. Accordingly, the integration efforts made by second-generation Afghans take place in and are impacted by a discriminatory environment. We found that failure in integration efforts is accompanied by a disconnection from the Afghan community, contributing to a sense of being “caught between two worlds” for these individuals, leading to deteriorating mental health. In response to their unfavourable circumstances, the second-generation Afghans adopt strategies, such as de-labelling their Afghans’ stigmatized identity, building new but purposeful social ties, and shaping a cosmopolitan identity.

In our journey of research, we uncovered some important aspects of Afghan immigrants’ experiences, as follows:

First, we learned that even those Afghans who were born in Iran and resemble their Iranian peers often feel a deep sense of rejection from Iranian society. This is somehow surprising, as one might expect that shared cultural traits would lessen hostility between groups. Yet, for many, the experience of feeling like an outsider persists. As we listened to their narratives, we noticed a common theme: many second-generation Afghans struggle with their attributed Afghan identity, reluctant to keep in touch with the Afghan community in Iran. This indicates that when their sense of belonging feels disrupted, they lose the emotional support that typically comes from being part of a group.

Moreover, this distancing is not only felt by the younger generations; older members of the Afghan community in Iran also pull away from them. This sense of separation felt by young Afghan immigrants makes it difficult for them to keep their connections with their own community in Iran. Finally, they find themselves caught between two worlds: neither accepted in the Afghan community nor in Iranian society. Our study provides evidence that similar cultural elements and shared language cannot guarantee pleasant intergroup relations and so facilitate the integration process.

To cope with these feelings of rejection, second-generation Afghans adopt various strategies. Some try to downplay their Afghan identity and, by doing so, escape negative stereotypes. Others seek out friendships with successful individuals or with those who share migration experiences to create a supportive network. Some may embrace a cosmopolitan identity, focusing on universal values that transcend national boundaries.

We recommend that policymakers prioritize the creation of more inclusive and welcoming environments to mitigate discrimination and promote positive intergroup relations. To facilitate smoother intergroup contact and integration, policies aimed at improving the socioeconomic status of second-generation Afghans and achieving more equal status with their Iranian counterparts are particularly recommended. These programs can include, but are not limited to, organizing cultural exchange events, improving education access, and establishing community centres and health and wellbeing programs.

Interested in learning more? You can access the published version of the paper here:

Keshavarzi, S., Jetten, J., Ruhani, A., Fuladi, K., & Cakal, H. (2024). Caught between two worlds: Social identity change among second-generation Afghan immigrants in Iran. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 34(5), e2881. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2881

About the author

Dr. Saeed Keshavarzi is a social psychologist and sociologist specialising in inter-group relations, collective action, social movements, identity processes, activism, and migration. He is a postdoctoral research fellow at Osnabruck University and holds a Ph.D. in sociology, with a focus on social groups. He is particularly interested in bringing scientific insights from disadvantaged and underrepresented groups into the sociology and psychology literature.

References

Ashrafi, A., & Moghissi, H. (2002). Afghans in Iran: Asylum fatigue overshadows Islamic brotherhood. Global Dialogue, 4(4), 89.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

Chatty, D. (2010). Deterritorialized youth: Sahrawi and Afghan refugees at the margins of the Middle East (Vol. 29). Berghahn Books.

Farahani, H., Nekouei Marvi Langari, M., Golamrej Eliasi, L., Tavakol, M., & Toikko, T. (2023). “How Can I Trust People When They Know Exactly What My Weakness Is?” Daily Life Experiences, and Resilience Strategies of Stateless Afghans in Iran. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2023.2199252

Haslam, C., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Cruwys, T., & Steffens, N. K. (2021). Life change, social identity, and health. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 635–661. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-060120-111721

Haslam, C., Jetten, J., Cruwys, T., Dingle, G., & Haslam, S. A. (2018). The New Psychology of Health: Unlocking the Social Cure. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315648569

Jetten, J., Haslam, S. A., Iyer, A., & Haslam, C. (2009). Turning to Others in Times of Change: Social Identity and Coping with Stress. In S. Stürmer & M. Snyder (Eds.), The Psychology of Prosocial Behavior (pp. 139–156). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444307948.ch7

Ruhani, A., Keshavarzi, S., Kızık, B., & Çakal, H. (2023). Formation of hatred emotions toward Afghan refugees in Iran: A grounded theory study. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000685

Sadeghi, F. (2008). Negotiating with modernity: Young women and sexuality in Iran. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 28(2), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1215/1089201x-2008-003

Sadeghi, F. (2024). Afghan Community in Iran: Five Decades On. https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/afghan-community-in-iran-five-decades-on-165046

Smeekes, A., & Verkuyten, M. (2015). The presence of the past: Identity continuity and group dynamics. European Review of Social Psychology, 26(1), 162–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2015.1112653